Global trends in greenwashing and sustainability claims

CMS Green Globe Team

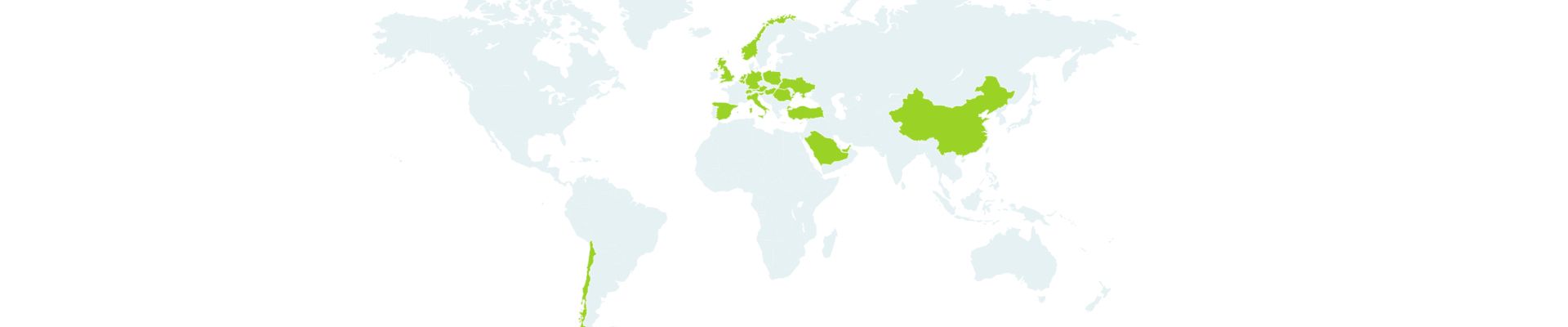

The greenwashing and sustainability claims trends presented to readers in our ‘CMS Green Globe’ greenwashing and sustainability guide differ from country to country. However, some common trends can still be identified amongst the various jurisdictions. Below are the three most commonly encountered trends that are currently being observed across the globe in relation to greenwashing and sustainability claims.

1. The emergence of detailed regulations and guidelines

The issuance of guidelines detailing the legislation already in place, coupled with the adoption of new relevant legislation in countries where greenwashing and sustainability claims are not yet fully regulated, is the most common trend that can be observed in most of the surveyed jurisdictions. This applies, among others, to territories including Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Hungary, Netherlands, Chile, Norway, Poland, Romania, and the United Kingdom.

In those jurisdictions where governments are proposing to introduce (or have recently introduced) further laws and regulations to combat the issue of greenwashing, the proposed new laws and regulations cover a varying scope of topics. For instance, in Austria, the legislator is planning to introduce stricter labeling regulations that apply specifically to the food industry, whilst the ‘Guidelines on Environmental Claims’ issued by the relevant Belgian regulator aim to provide clarity on how to apply general (and somewhat vague) principles that are currently in place.

Some jurisdictions do not limit their focus solely to regulating the behavior of businesses and traders, but also try to increase public awareness of the issue of greenwashing. The Hungarian Competition Authority, for example, has issued both the ‘Green Marketing Guidance for Undertakings’ and a public-facing communication drawing the attention of consumers to the need to always double-check the accuracy of sustainability claims made by advertisers.

By contrast, some jurisdictions demonstrate the opposite position, reporting a notable lack of (and/or vagueness of) laws and regulations governing greenwashing and sustainability claims. In China, for example, despite the fact that the legal system governing environmental protection is improving, legislation on greenwashing is still largely absent.

Nevertheless, for the majority of the surveyed jurisdictions, the primary trend is the further development of laws and regulations targeting greenwashing and sustainability claims.

2. Greater public pressure and consumer awareness

Many jurisdictions indicate that efforts to combat greenwashing and misleading sustainability claims are increasingly driven by the public. In most countries, the growth of consumer awareness on the subject, as well as an increased readiness of consumers to take action in this regard, represent another notable trend in the area of greenwashing and sustainability claims. Increased public pressure of this nature can be observed most significantly in jurisdictions such as China, Germany, Hungary, Norway, Romania and the United Kingdom.

In many instances, public influence is ultimately implemented through action by competition and consumer protection organisations and associations. In Germany, for example, the ‘German Centre for Protection against Unfair Competition’ and the ‘Deutsche Umwelthilfe’ (Environmental Action Germany) have successfully taken action against businesses using misleading environmental advertising claims (namely, climate neutrality and recyclability statements).

Another jurisdiction in which there has been a significant increase in public awareness and consumer pressure in this area is the United Kingdom. Recently, non-governmental organisations such as ‘AdBlock Bristol’ and ‘AdFree Cities’ have been active in this sector and have, amongst other things, lodged a formal complaint with the Advertising Standards Authority in relation to a series of adverts published by a leading bank, which they argued were “greenwashing by omission” (such complaint ultimately leading to the regulating authority upholding the complaint).

As with the first common trend above, there are also exceptions to the rise in public pressure and consumer awareness. Consumers in some jurisdictions seemingly ‘lag behind’ in terms of their awareness and interest in greenwashing and sustainability claims. One such jurisdiction is the Netherlands, where a recently published study revealed that knowledge about the difficulties associated with green claims is very limited amongst Dutch consumers. The same anomaly has also been observed in Poland.

Overall, public interest in greenwashing and sustainability claims remains at a fairly high level, and is being further promoted by both government bodies and non-government organisations through various initiatives, including, for example, study programmes (as is the case in Spain).

3. Increased scrutiny of greenwashing and misleading sustainability claims by authorities

Another common trend in relation to greenwashing and sustainability claims is an evident increase in the amount of scrutiny applied by government authorities. For example, stricter enforcement and a higher level of applicable fines has been observed in countries such as the Czech Republic, Germany, Norway, Romania, Switzerland, Ukraine, and the United Kingdom.

For instance, in recent times, Switzerland's financial markets regulator has specified transparency obligations regarding climate risks, and has promoted transparency in order to avoid greenwashing and misleading the public about products’ sustainability characteristics.

The Ukrainian Competition Authority has also been increasing the attention it gives to greenwashing and sustainability claims by businesses in recent years. It has, for example, broadened the scope of information that is classed as ‘misleading’ in relation to sustainability claims, which has resulted in several companies’ activities being found to amount to dissemination of misleading information and thus constitute greenwashing.

Finally, certain other jurisdictions show an increase in regulatory authorities focusing on specific industries. In Norway, for example, the regulatory authority has recently been turning its attention specifically to the usage of green claims by fashion retailers. In Romania, by contrast, it is the agricultural sector that is receiving the focus of the relevant authorities, where the Unfair Trading Practices Directive has been transposed into Romanian law and triggered significant changes in the industry.

_840x420px%20(1).jpg)